The Art of Muon Collisions

Tova Holmes, Larry Lee, and Charles Bell

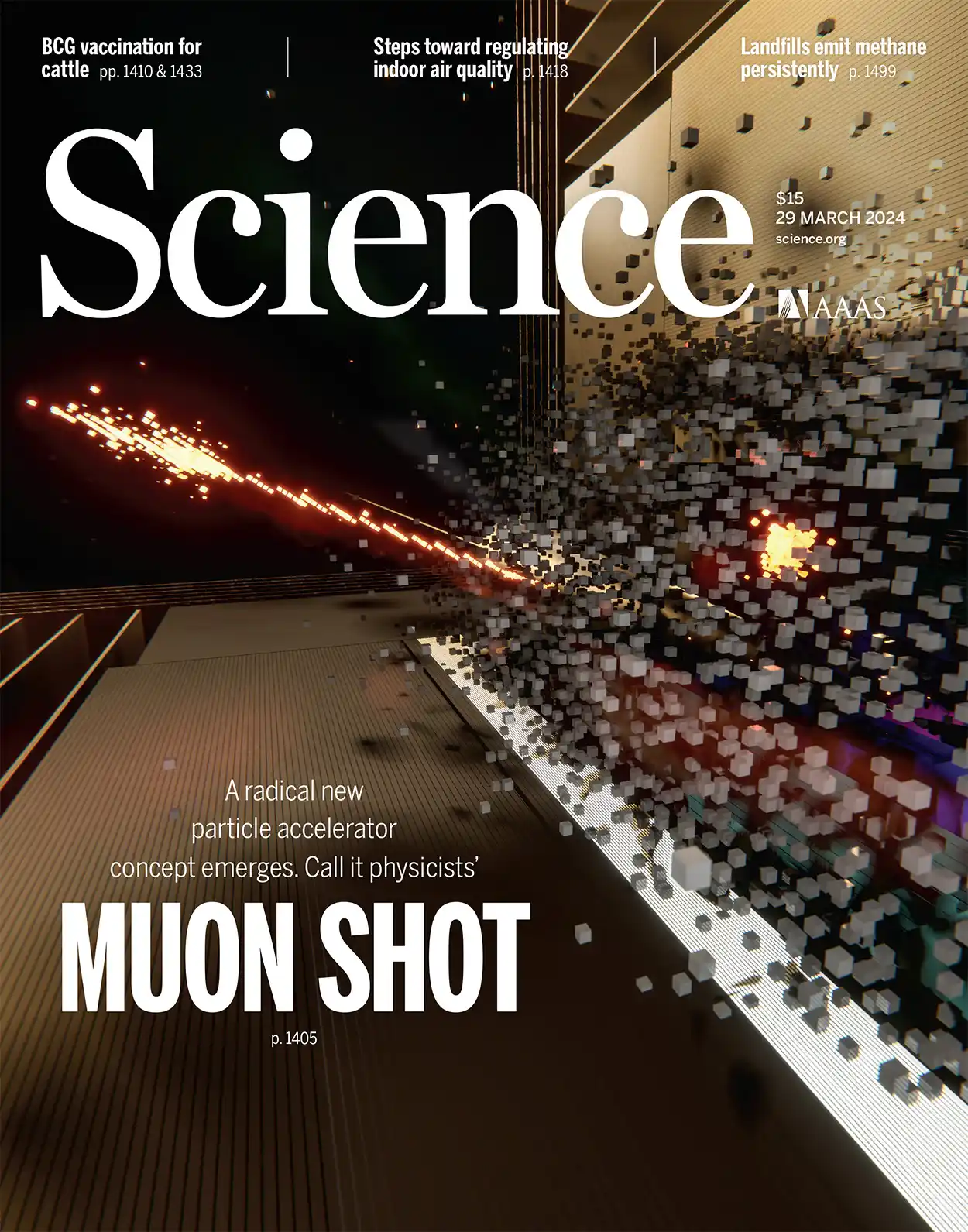

Assistant Professors Tova Holmes and Larry Lee are particle physicists and in their line of work, to think big, you have to think small. That’s where muons come in, and it’s how they became part of a Science Magazine story—including creating the cover art.

In “The Dream Machine,” journalist Adrian Cho reviews the newly-drawn roadmap for particle physics research in the United States. For the past century, physicists have designed, built, and deployed powerful accelerators that rev up and collide particles, precisely measuring the fragments and tracking the escapees to learn more about the building blocks of matter that make up the universe. With current instruments here and abroad reaching their energy limits, American physicists are looking at three possible types of colliders to replace them. Among them is a muon collider.

Will the Muon Have Its Moment?

Muons are fundamental particles. They’re quite a bit like electrons, but roughly 200 times heavier. Until now protons and electrons have been the particles of choice for collider physics, but with their extra mass muons are good candidates for collisions at energy scales up to 10 times higher than that of the Large Hadron Collider, the current world leader. As an early-career scientist, Holmes explained to Cho that waiting something like another five decades for a next-generation collider means the particle physics research she’s so passionate about would pass her by.

“I will be definitely not still working, possibly not alive,” she said.

That’s why she and Lee have spent nearly four years creating designs for a possible muon collider. Holmes coordinates the US-based research and development program for tracking detectors. (Her work has won her a Department of Energy Early Career Research Award, as well as place among the 2024 Class of Cottrell Scholars.) In her conversation with Cho she referred him to Lee as a source for images that could further describe the muon collider vision and enhance the article. Like Holmes, Lee has a strong belief in the power of imagery to convey scientific concepts, so he gladly accepted the assignment.

Renaissance and Romance

Planning for a muon collider is one thing. Promoting the idea to stakeholders is another. Holmes and Lee saw right away that the imagery accompanying those pitches didn’t always match the excitement for the collider’s promise.

In particle physics, “we have a long history of making what are called event displays,” Lee explained, which are simply visualizations of individual collision events. He said scientists have field-specific tools to create those displays, but the results look technical and aren’t particularly engaging.

“One thing I’ve wanted to do for a long time was bring in modern 3D environment modeling to essentially do the same thing, but in a slicker way,” he said.

With UT’s particle physicists’ involvement in the muon collider—specifically a conceptual design for a detector—he saw a fantastic opportunity.

“Right now, if we’re talking about the detector, we’re just in the design phase,” Holmes explained. “We write down some parameters, we try and visualize it, we simulate it, we shoot fake particles into it in our simulation, (and) we see what we can do to reconstruct it.”;

Lee enlisted Undergraduate Physics Major Charles Bell to help create a visualization of the detector and what the particles inside it might look like. They started with proprietary formats familiar to particle physics and brought in industry standard tools, ultimately incorporating Unreal Engine, a creative suite used for an array of simulation purposes. The resulting images were stunning enough to land on the cover of Science and alongside Cho’s article.

While standard event displays are great for showing off technical details, the new artistic images add another layer of strategic communication.

“Larry was trying to make a version of them that took advantage of all the tools that are out there to make them both useful and beautiful,” Holmes said. “Improving this kind of visual translation is really important for the future of our field because we have to be able to explain the kind of exploration we’re doing through visual media.”

Holmes said the muon collider’s success is dependent on audiences both inside and outside physics. At present only a few hundred scientists the world over are involved in the project.

“There have been past versions of this muon collider effort where the technology was not really close enough to ready for people to take it seriously as the next thing,” she said. “It needs to grow to happen. That means getting more people interested. It also needs the engagement of the field to get support from funding agencies. Being able to communicate clearly the excitement, and make sure that communication gets in people’s laps, matters.”

She’s hopeful Lee’s images will inspire a “renaissance” where researchers look at the technological progress surrounding the muon collider and see its potential in a new light. They both also want the public to become more excited about the science behind, literally, everything.

“In astrophysics it’s very easy to visualize because we take literal photographs of the universe,” Holmes said. “For us (in particle physics), we can’t take literal photographs. We do something similar with our detector reconstruction, but it doesn’t look like a photo.”

Lee said he wants images like those he created for the muon collider project to tie in to the “romantic big picture” of fundamental science and capture human imagination.

“We both feel very strongly that it’s important to make things visually compelling, because once you do, people remember them,” he said, even if they don’t fully understand the science behind the pictures.

“This was something we’ve been talking about in the muon collider effort because you’re asking the public to embrace a big project and if you can’t explain what it’s for, you have a real problem,” Holmes said.

This isn’t her first foray into art where the collider’s concerned: she created a poster that’s hanging in a good many physics departments as well as swag to promote the project.

Holmes and Lee believe that prioritizing compelling science communication isn’t just a feel-good pursuit: it’s a key to helping serious science thrive.

“This work is important,” Lee said. “It’s not purely outreach; it’s not purely just for fun. It really pushes us to the literal front of the journal.”

Terms and Conditions re: reprinted AAAS material: Readers may view, browse, and/or download material for temporary copying purposes only, provided these uses are for noncommercial personal purposes. Except as provided by law, this material may not be further reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, adapted, performed, displayed, published, or sold in whole or in part, without prior written permission from the publisher.