UT’s Biophysics Group Investigates How Chromosomes Separate

Biologically speaking, family stories are written in chromosomes. For the story to continue, those chromosomes have to be copied and passed on to the next generation. In recently published findings, UT’s biophysicists took a deeper look at how this works in Escherichia coli (E. coli) to better understand the process.

A Simple System with a Multi-Step Process

Chromosomes are long strands of DNA that wrap around proteins. A key part of a cell’s life cycle is chromosome replication and the transfer of genetic material to daughter cells. Professor Jaan Mannik’s and Adjunct Assistant Professor Max Lavrentovich’s groups wanted to understand how that mechanism is organized and carried out in bacteria (specifically E. coli).

“Chromosomes must be equally divided between the two daughter cells during cell division, otherwise the cell that lacks a full genome will die,” Mannik explained. “In human cells, the mitotic spindle is responsible for separating the chromosomes before cell division starts. However, bacteria lack a mitotic spindle. The question arises how the bacteria separate their chromosomes.”

He explained that “it is expected, based on polymer physics models, that two new DNA strands forming during replication in cylindrical confined conditions repel from each other due to an entropic force (entropic segregation mechanism).”

The Upside of Unmet Expectations

Graduate student Chathuddasie I. Amarasinghe (a first-time first author) took on the challenge to test this mechanism experimentally. She was joined by Graduate Student Mu-Hung Chang, who tackled the same question via modeling.

Using high-throughput fluorescence microscopy, Amarasinghe said the group imaged thousands of cells using microfluidic devices (also called lab-on-a-chip) in a single experiment.

“We take time-lapse images of our cells and then use MATLAB and Python functions to analyze the data in different ways, both quantitatively and qualitatively, including still images and movies,” she explained.

Amarasinghe said when she first created this new strain of cells with a fluorescent tag on ribosomes, she “expected it to produce very straightforward results that would match theoretical predictions from the entropic mechanism perfectly.”

That wasn’t exactly what happened.

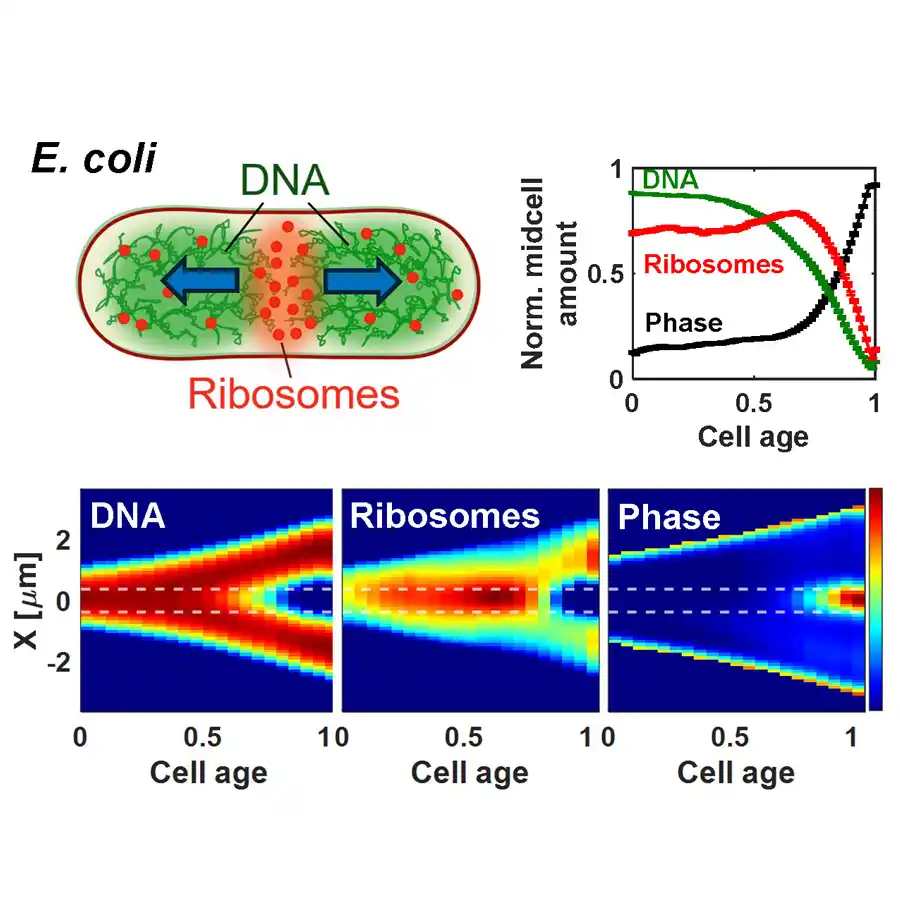

Working on the experiment she learned of another model proposing how the dynamics of mRNA–ribosome complexes could affect DNA segregation. Messenger RNA copies genetic material from a DNA strand and carries that information to the ribosome, which makes proteins. Amarasinghe et al. found that once the replication process is roughly at the halfway point, the accumulation of messenger RNA and ribosomes in the middle of E. coli chromosomes becomes strong enough to start driving the two daughter DNA strands away from each other. This process continues past the point when the two chromosomes lose contact with each other and separate.

In parallel to this process, Amarasinghe and co-workers found that the daughter chromosomes are also separated by the closing constriction, a final “pinching” of the cell. During constriction the cell envelope bends inward and physically pushes the chromosomes apart.

The evolution of chromosome separation in E. coli. Top left: Diagram of an E. coli cell showing polysomes pushing sister chromosomes apart. Bottom: Heatmaps show cell-cycle-dependent changes in DNA and ribosome density distributions, and constriction formation. The top right corner shows normalized mid cell amounts from these heatmaps (integrated between the dashed horizontal lines).

Chang led development of the model, which used partial differential equations to describe the evolution of DNA, polyribosomes, and ribosomal subunits in E. coli cells.

The results of the experiment are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. PNAS is a peer-reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences covering the biological, physical, and social sciences. In addition to Amarasinghe (first author), Chang, Lavrentovich, and Mannik, other contributors are Jaana Mannik (a research scientist with UT Physics) and Scott T. Retterer of Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Diving into Deep Questions

Biophysics captured Chang’s attention during his first year in the physics graduate program. Lavrentovich (then on UT’s faculty) introduced his work to new students, and Chang said “the mysterious phase transition patterns occurring in living beings attracted me.”

Within a couple of years, he joined the biophysics group.

“I started studying the organization pattern of E. coli DNA, which shows phase separation behavior between different species similar to some phase transition patterns Max showed before,” he said.

Chang defended his PhD dissertation this fall and will continue working with the Mannik group while applying for postdoctoral positions.

Amarasinghe came to biophysics a little earlier, taking a biophysics course as an undergraduate.

“For my undergraduate research, I developed antimicrobial packaging materials, which gave me hands-on experience with microbiology techniques that confirmed my interest in microbial research,” she said.

When she came to UT for graduate studies and learned of Mannik’s research, she was immediately interested in becoming part of the work.

“His research focuses on understanding how life self-organizes from seemingly simple components using the model organism E. coli, which is one of the deepest open questions in biology,” she said.