Where Are Your Memories Stored?

Dima Bolmatov explains in The Conversation

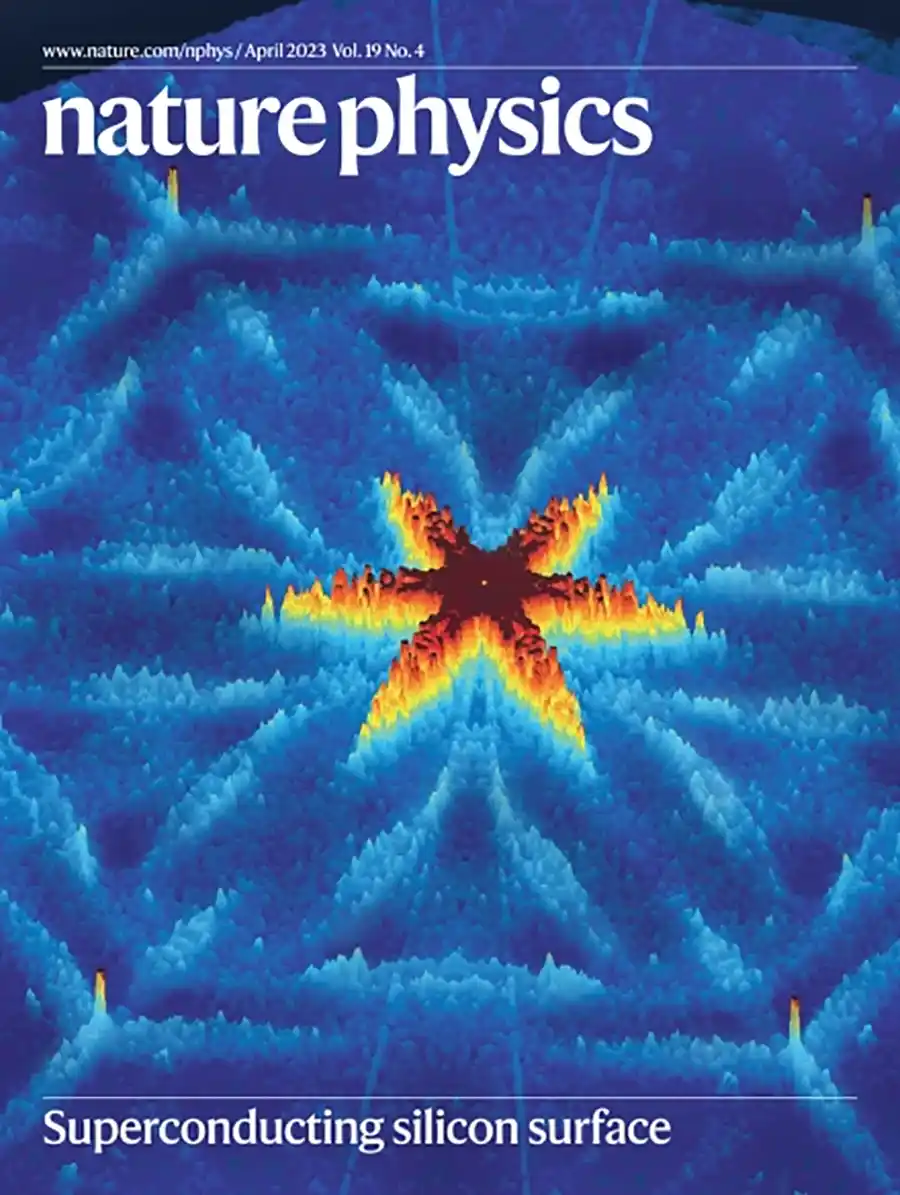

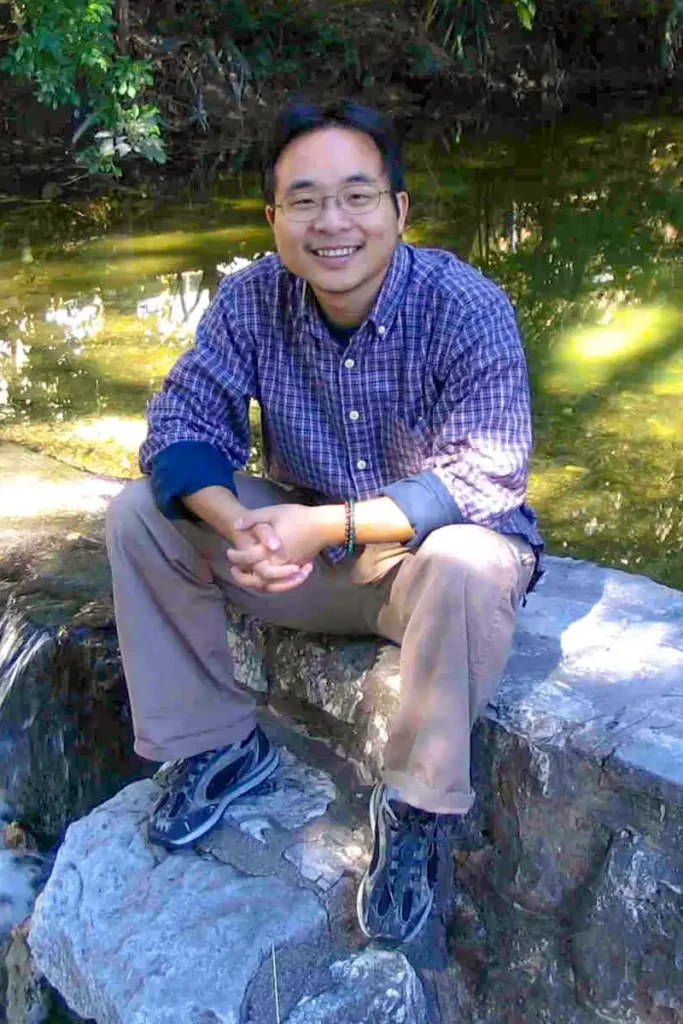

You may easily remember your kindergarten teacher, your brother’s birthday, or how to do long division. But how? Why do these things get filed away in a place you can quickly access while other information gets lost? Research Assistant Professor Dima Bolmatov helps explain the biophysics of memory for The Conversation in Memories May be Stored in the Membranes of your Neurons.

The article takes findings reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and reframes the science for a general audience. The original research concerns the physics of the brain’s infrastructure and how it influences learning and memory. Understanding how our brains encode information for retrieval has implications for both medicine (Alzheimer’s and dementia research) and computing (developing the neural networks that drive machine learning).

Bolmatov joined the physics department in 2020 and works with the Shull-Wollan Center (SWC) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The center connects him with the requisite tools (e.g., X-ray and neutron scattering) to study biological systems at the molecular level. His research links biophysics and soft condensed matter and he collaborates with Assistant Professor Max Lavrentovich and Professor Alan Tennant as well as colleagues in biology, psychology, and materials science.