New Quantum Networks Research and Training Program Receives $3M NSF Award

Courtesy of Professor George Siopsis

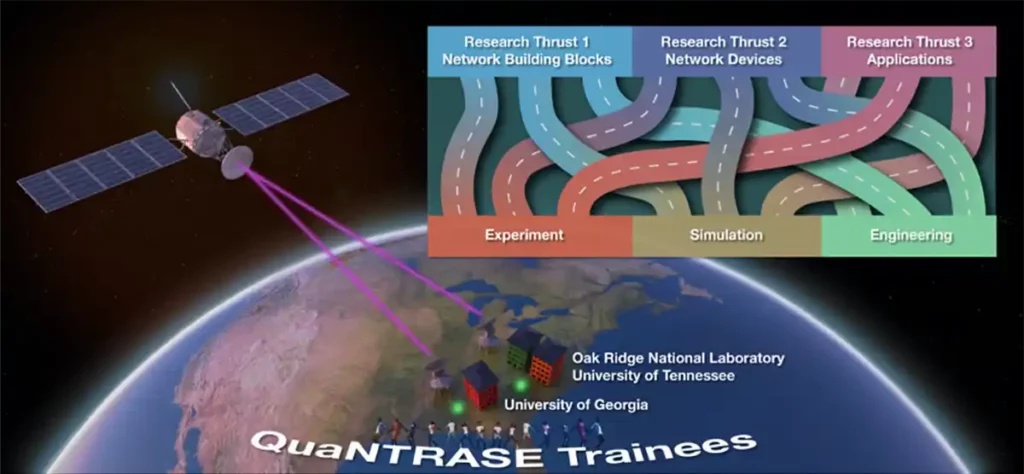

The National Science Foundation Research Traineeship Program (NRT) awarded a $3 million Collaborative Grant to the University of Georgia (UGA) and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, to develop a Quantum Networks Training and Research Alliance in the Southeast (QuaNTRASE).

The NSF award advances convergent research in quantum information science and engineering, which it has identified as a national priority of utmost importance, via training graduate students through a comprehensive traineeship model. The program supports graduate students, educates the STEM leaders of tomorrow, and strengthens the national research infrastructure.

“NSF continues to invest in the future STEM workforce by preparing trainees to address challenges that increasingly require crossing traditional disciplinary boundaries,” said Sylvia Butterfield, acting assistant director for NSF’s Directorate for Education and Human Resources. “Supporting innovative and evidence-based STEM graduate education with an emphasis on recruiting and retaining a diverse student population is critical to ensuring a robust and well-prepared STEM workforce.”

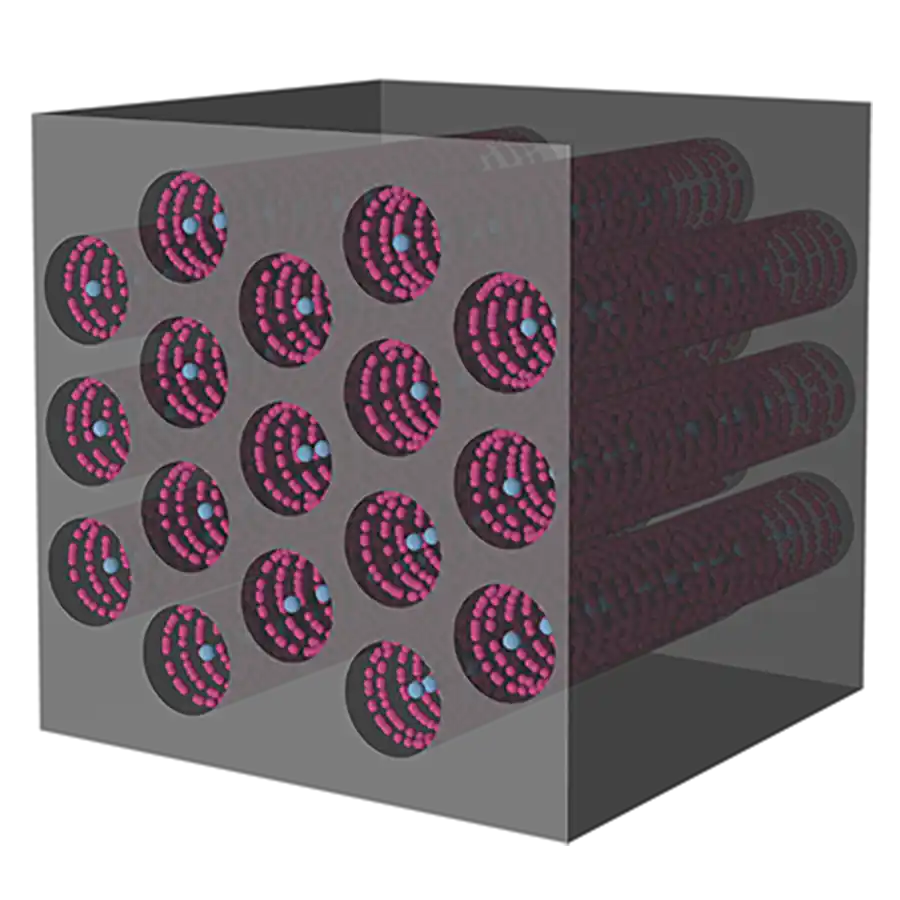

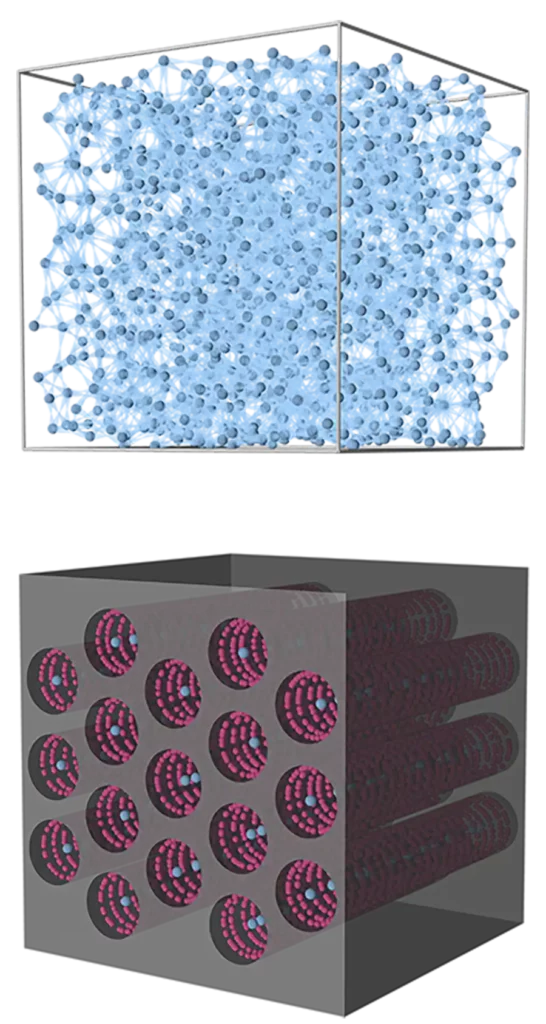

Quantum networks promise a novel and more secure functionality than the classical networks on which current communication encryption technologies are built. Developments surrounding quantum networks include fundamental discoveries in quantum science as well as key applications in cybersecurity, quantum sensors, and quantum computing.

“To realize the promised advantage of a quantum internet, many fundamental science and engineering challenges must be overcome via a convergent combination of expertise from several science and engineering disciplines and the development of a well-trained, interdisciplinary quantum network workforce.” said Yohannes Abate, Susan Dasher and Charles Dasher MD Professor of Physics at UGA. “The goal of this program is to advance quantum networks research through the design and development of components and applications of quantum networks.”

“The program is one of the first comprehensive, interdisciplinary quantum information science and engineering (QISE) training programs in the Southeast.” said George Siopsis, professor of physics at UT and director of the university’s Quantum Leap Initiative.

This joint UGA-UT effort, in collaboration with Oak Ridge National Laboratory and industry partners, will expand the diversity of students in quantum information science and engineering, including historically underrepresented groups.

“The strength of QuaNTRASE is our capacity to integrate the quantum networking expertise from two major research institutions with a national laboratory to advance research and prepare trainees for the developing quantum economy,” said Tina Salguero, professor of chemistry at UGA.

The program will develop MS and PhD programs via five key elements of the education and training frameworks: (i) the development of a curriculum that integrates interdisciplinary and cross-institutional course offerings; (ii) the incorporation of vibrant cross-institutional and interdisciplinary advising and mentoring; (iii) the introduction of quantum technology concepts into existing science and engineering disciplines; (iv) research rotations, which will enhance students’ experience in quantum networks; and (v) additional professional development through national laboratory and industry-university partnerships, a trainee-led career fair, research retreats, and summer internships. This interdisciplinary collaboration will be a core component of the QuaNTRASE research program.

In addition to the scientific activities, the project will develop and deliver STEM outreach activities for local high school students and teachers focused on quantum concepts, careers, and practices through summer and after-school STEM programming.

“Preparing future generations for jobs in the quantum and AI fields is a national priority,” said Mehmet Aydeniz, professor of STEM education at UT. “By reaching out to high school students and introducing them to quantum concepts, practices and careers early on, we aim to prepare the scientists and engineers of the future, who will be instrumental to the nation’s leadership in science and quantum computing specifically.”