How Spin Shapes the World

Assistant Professor Dien Nguyen has won an Early Career Award from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, an $875,000 investment in understanding how materials are arranged at the fundamental level.

Giving Order to the Universe

While a touchdown pass or a Smoky Mountain waterfall is a big (and splashy) display of physics in action, Nguyen’s work gets down to the microscopic scale—the nuts and bolts of matter. This is quantum physics, where predictions are difficult to make and events are hard to explain.

An atom is pretty complicated on its own, but its smaller components are even more complex. Inside there’s a nucleus comprising protons and neutrons (known together as nucleons). Nucleons are made up of still smaller particles called quarks, bound together by gluons. Then there’s spin, a fundamental property of nucleons. That’s what Nguyen studies, going a step beyond the basic building blocks of matter.

“It’s not just the building,” she said. “It’s fundamental structure. Spin is responsible for shaping the world—a provider of order and structure to the universe.”

Spin determines, for example, how materials are arranged, down to their most basic level. The more clearly scientists understand how that works, Nguyen said there’s greater potential to apply those findings to fields like materials science, medicine, and quantum computing. Despite its promise, identifying the origin of nucleon spin has been a longstanding challenge in nuclear physics. While physicists have studied both proton and neutron spin, the latter has gotten far less attention.

“Experimentally, neutron spin is way harder to study compared to proton spin,” Nguyen explained, adding that scientists need to understand both to get a clear picture of how matter is ordered. Her work is helping fill the gap by focusing on the neutron at the quark level.

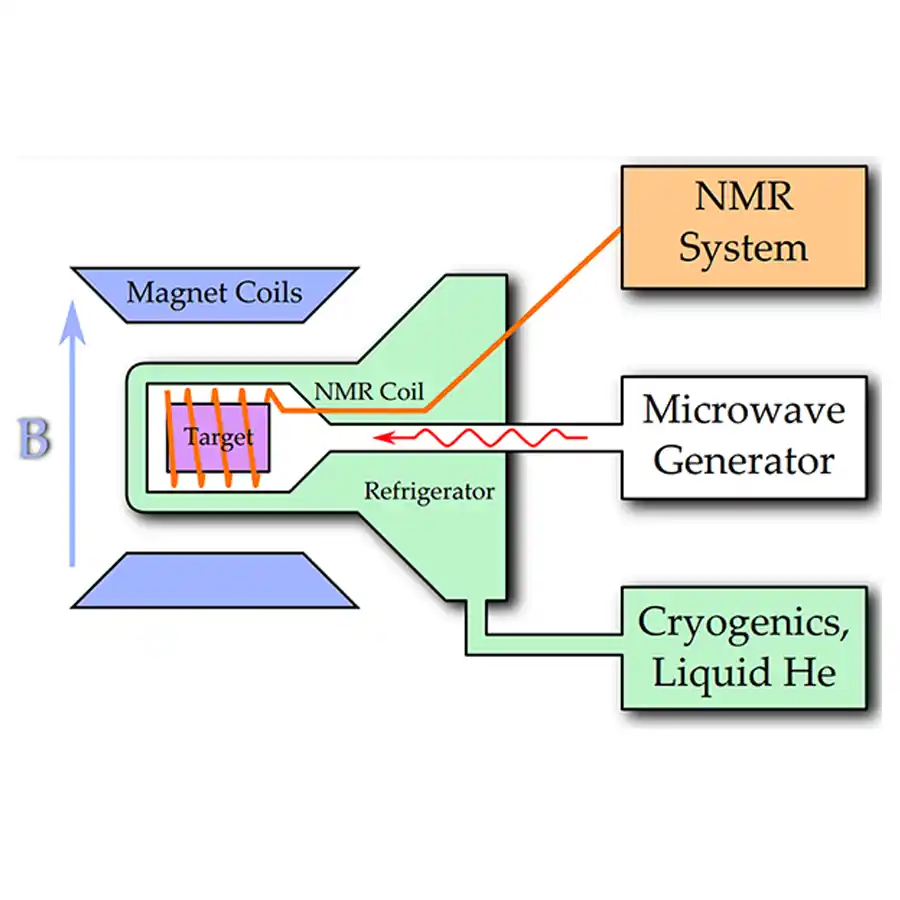

By scattering electrons from a polarized Helium-3 target, Nguyen can provide high-precision data that helps her understand the quark’s internal structure and dynamics (including spin of its own) and how those influence what happens with nucleons. That information helps her map quark spin and how it in turn affects neutron spin.

“I’m bringing missing pieces,” she said. Once all is done, “we should have a much better understanding of the fundamental structure of matter.”

The DOE award will support this work, which includes collaborations with Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). It will also help Nguyen bring her campus lab up to speed and hire a postdoc and a graduate student so that she can train young scientists in experimental nuclear physics.

A Grateful Vol

Mentoring is a skill Nguyen developed from her own experience. It’s also how she got interested in neutron spin studies.

“I was always interested in this challenging spin study, but did not get a chance to touch it until I went to MIT after my PhD,” she said.

When she was a postdoctoral fellow at MIT’s Laboratory for Nuclear Science, her office was next door to that of Richard Milner, who co-authored a book about physicists’ quest to understand spin and the structure of matter. She began asking him questions about the research and eventually he asked if she wanted to work on a project with him.

“I’m on board,” she told him.

A self-described “hands-on person,” Nguyen said when Milner explained this kind of physics would require a target, she dove in. That was part of her work as a Nathan Isgur Fellow at JLab, where she began working with the Target Group. From there she accepted a bridge position between UT Physics and Jefferson Lab, becoming part of the university’s faculty in 2024.

Nguyen said she’s grateful for the guidance that’s helped define her path. She’s quick to name her advisors: Donal Day, Or Hen, Douglas Higinbotham, and many others, all of whom had different approaches. Some offered unconditional support while others pushed her by setting high standards and tight deadlines. She explained how James Maxwell welcomed her at Jefferson Lab and taught her “everything from the first step about target polarization,” while Milner opened “the bigger view and let you decide what you want to do.”

Taken together, she said, “it’s kind of a mix and really impacted my style of mentoring. I take pieces of that.”

That method has worked well for Nguyen. The UT Graduate Physics Society selected her as their Research Advisor of the Year for 2025.

“This is one of the more important awards for me because it makes me feel like I’m doing things right,” she said. “One of the reasons I wanted to be a professor is that I like to work with students and I like teaching. I put a lot of effort into that. When the students recognize that I care about them, that makes me really happy.”

She’s also not through learning herself. When she first arrived at UT in 2024, Professor Nadia Fomin showed her the ropes of faculty life.

“Nadia taught me a lot,” she said. “She’s a great mentor and I’m thankful to have her here. She took a lot of time on my (DOE Early Career Award proposal) draft and gave me feedback, and I really appreciate that. That was definitely an important piece for this award. I tell her that we won it, not that I won it.”

Nguyen’s success continues an upward trajectory for UT physics in bringing outstanding scientific talent to campus. This is the second DOE Early Career award for the department since 2022, when Associate Professor Tova Holmes won support for her research in elementary particle physics. The program supports outstanding scientists early in their careers whose work furthers DOE Office of Science research priorities.

Professor and Department Head Adrian Del Maestro explained that “Early Career Awards recognize only the brightest and most innovative junior faculty in the United States. Assistant Professor Nguyen is exemplary in terms of both her vision and the impact she has already had on our nuclear physics program. As a bridge faculty, she is representing UT at one of the country’s most elite scientific laboratories. We are excited to see what she will accomplish with this well-deserved award right at the beginning of her career in Knoxville!”

Nguyen said the physics faculty and staff have created a friendly atmosphere that makes coming to work a pleasure.

“I feel welcome when I’m here,” she said. “They make my life here much more beautiful.”