Alumni Association Honors Lee and Siopsis for Teaching and Distinguished Service

Joon Sue Lee and George Siopsis joined UT nearly three decades apart, but their shared commitment to the university’s mission transcends generations. The University of Tennessee Alumni Association (UTAA) has honored that dedication by recognizing Lee with an Outstanding Teacher Award and Siopsis with a Distinguished Service Professorship.

“The department was delighted to learn about the well-deserved alumni recognitions for Assistant Professor Joon Sue Lee and Professor George Siopsis, who both exemplify our training and knowledge-creation mission,” said Adrian Del Maestro, professor and department head. “Their passion for teaching and research in quantum technologies has played a large role in UT’s growing national and international prominence in this exciting area crucial for U.S. competitiveness.”

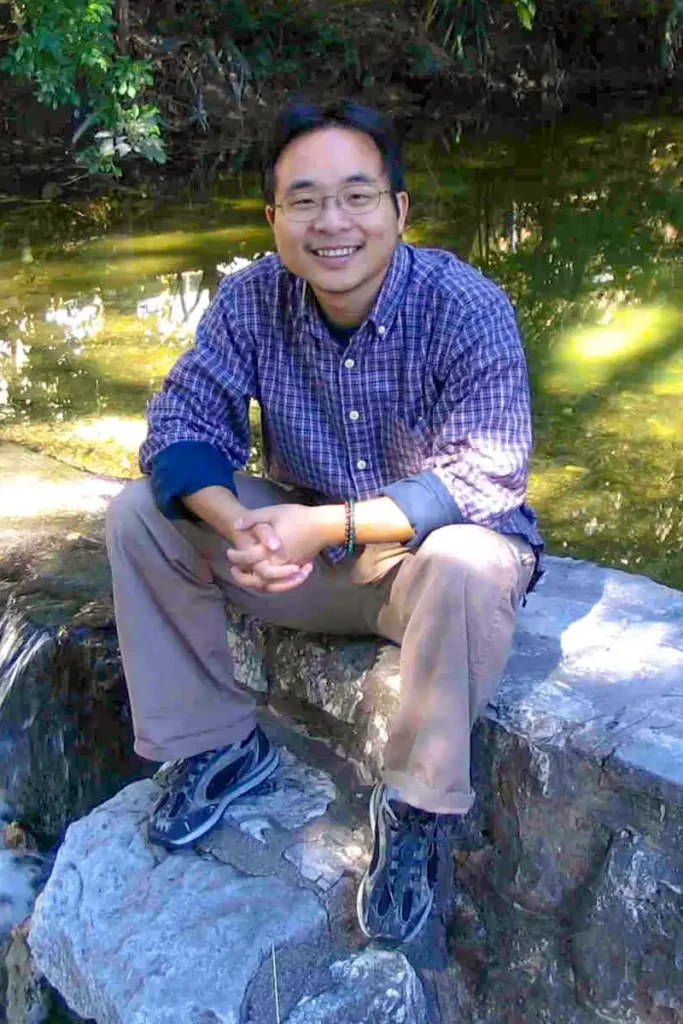

Developing Self-Reliant Thinkers

This is the second teaching honor this year for Lee, an assistant professor. UT’s College of Arts and Sciences presented him with an Excellence in Teaching Award at the annual faculty convocation. Since joining the physics faculty in 2020, Lee has taught undergraduates enrolled in Thermal Physics, Electricity and Magnetism, Electronics Lab, and Modern Physics Lab. His approach—especially to teaching labs—equips students with an understanding of physics fundamentals as well as the hands-on experience they need for careers in academe, technology, and industry.

“What has surprised me most about teaching is the impact that a collaborative and supportive learning environment can have on students’ engagement and development,” he said. “I have seen how nurturing critical thinking and fostering a dynamic partnership can transform the learning experience, and witnessing this has been greatly rewarding.”

Lee’s teaching isn’t limited to the classroom. His research centers on developing quantum materials and devices. Students in his group learn from and contribute to the work.

“What I like best about teaching is the opportunity to guide students as they navigate complex concepts and develop into self-reliant thinkers,” he said. “Mentoring students in my research lab and seeing them grow into independent researchers through the continuous exchange of ideas and collaborative processes is deeply fulfilling.”

Because the UTAA awardees are selected by a committee comprising alumni, Student Alumni Associates, and prior honorees, Lee and Siopsis were chosen in part by their peers, which Lee said is profoundly meaningful.

“The acknowledgement from my fellow faculty members, who understand the complexities and challenges of teaching, affirms the dedication and effort I put into creating an effective learning environment,” he said. “Additionally, being chosen by UT graduates highlights the impact of my teaching, extending beyond the classroom and into the students’ lives as alumni.”

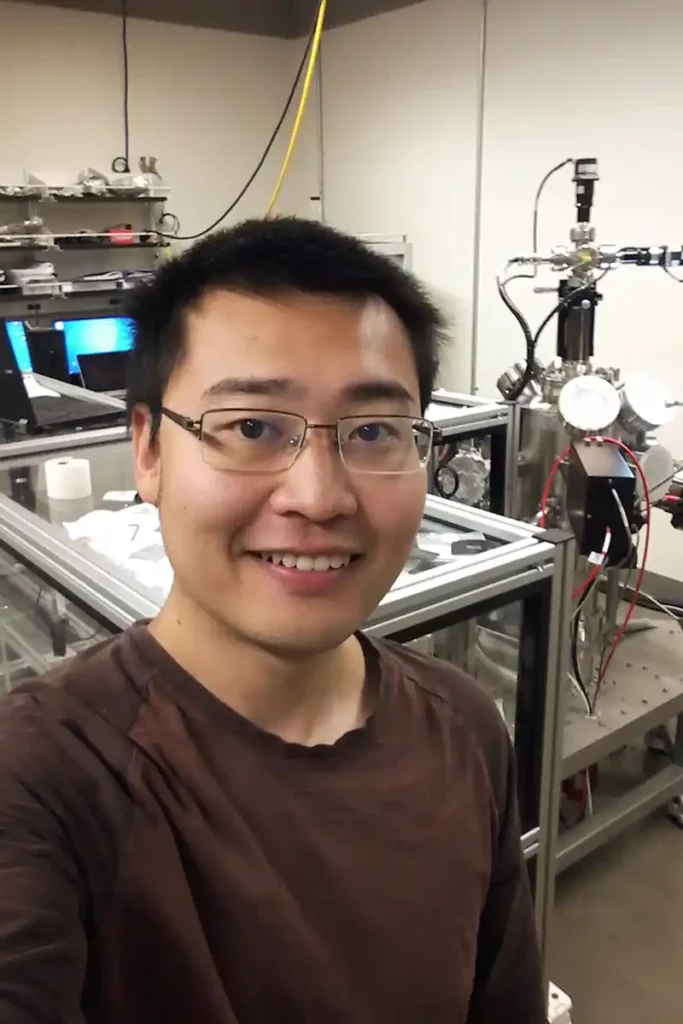

Nurturing the Next Generation

For Siopsis, the UTAA Distinguished Service Professorship has encouraged him to reflect on his many accomplishments while thinking about what comes next.

“Receiving this distinguished faculty award makes me feel deeply honored and appreciated,” he said. “It’s a mix of gratitude, validation, pride, humility, motivation, and a sense of responsibility. This recognition not only celebrates past achievements but also inspires me to continue making meaningful contributions to my field, the broader academic community, and the UT family.”

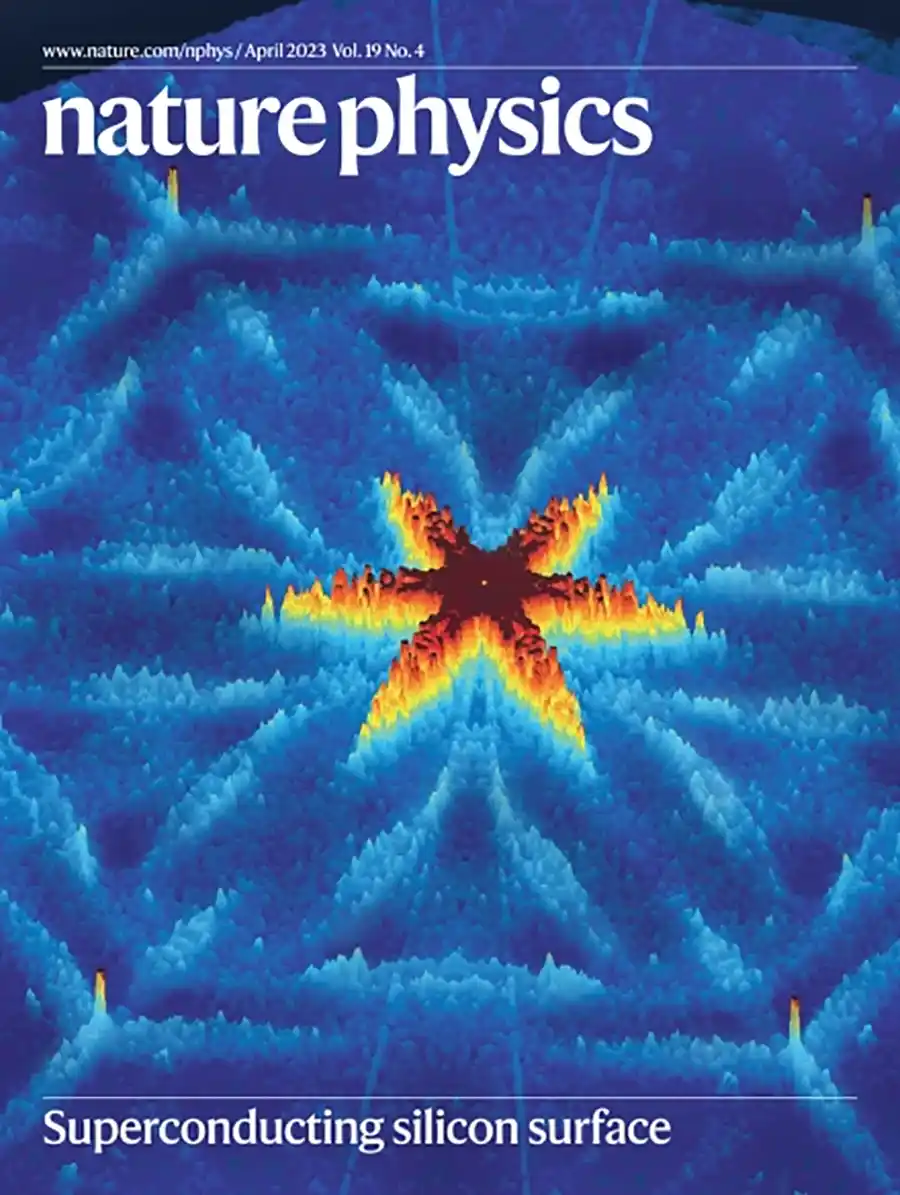

Siopsis came to UT Physics in 1991 and has balanced teaching, research, and service ever since. He’s taught courses from the fundamental (Elements of Physics) to the complex (Quantum Field Theory). He’s served as director of the Governor’s School for the Sciences and Engineering. A theoretical particle physicist, he specializes in quantum computing and networking, which heavily influences his current priorities. He’s built strong collaborations with partners from other universities, industry, and national laboratories with two aims in mind: developing quantum network applications and drawing on this emerging field to foster economic and technological growth in Appalachia.

Of all his endeavors, Siopsis said he is most proud of his leadership role in the Appalachian Quantum Initiative (AQI) and his work to bring UT to the forefront of emerging quantum technology. The AQI connects university researchers in the Southeast with industry partners to develop quantum software for scientific and engineering applications. This includes a quantum curriculum and workforce development component in partnership with other universities, industry, and national labs. In that vein, he and colleagues from the University of Georgia won $3M from the National Science Foundation to launch an interdisciplinary training program for graduate students. Siopsis develops and teaches classes and seminars in quantum technologies and is currently supervising or co-supervising the work of 11 graduate students.

This, he said, is part of his dedication to “nurturing the next generation of scientists in the emerging quantum field.”

Siopsis also draws on his expertise to lead a university-national laboratory project to develop a quantum regional network and pointed out that the Knoxville Chamber included the installation of a quantum network from Oak Ridge National Laboratory to UT as a goal in their 2030 Protocol plan.

Siopsis and Lee were recognized with their fellow awardees at a Faculty Awards Dinner on May 31. The UTAA presented 11 Outstanding Teacher Awards, two Public Service Awards, and six Distinguished Service Professorships this year, honoring outstanding faculty from across the University of Tennessee family. The association serves more than 445,000 graduates of the UT system through networking opportunities, legislative advocacy, career services, and alumni benefits, among other initiatives.