Tying Multiscale Physics to Bedrock Theory

Imagine standing on a seashore, watching the waves roll in. Now imagine trying to describe what’s happening inside a wave, an eddy, and a single drop of water—all at one time.

That’s the kind of challenge Professor Thomas Papenbrock and Adjunct Assistant Professor Gaute Hagen are up against as they calculate physics at different energy scales inside an atomic nucleus. With colleagues from Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Louisiana State University, and Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, they’ve developed a model that not only computes multiscale physics, but does so drawing from the roots of fundamental nuclear theory.

This kind of research is important because the more researchers discover about the nucleus, the better chance that knowledge can find its way to improving our lives (medical imaging and food safety) and answering bigger scientific questions (what fuels a massive star?). Those applications require understanding the essential properties of these complex systems.

Calculating Nuclear Waves and Eddies

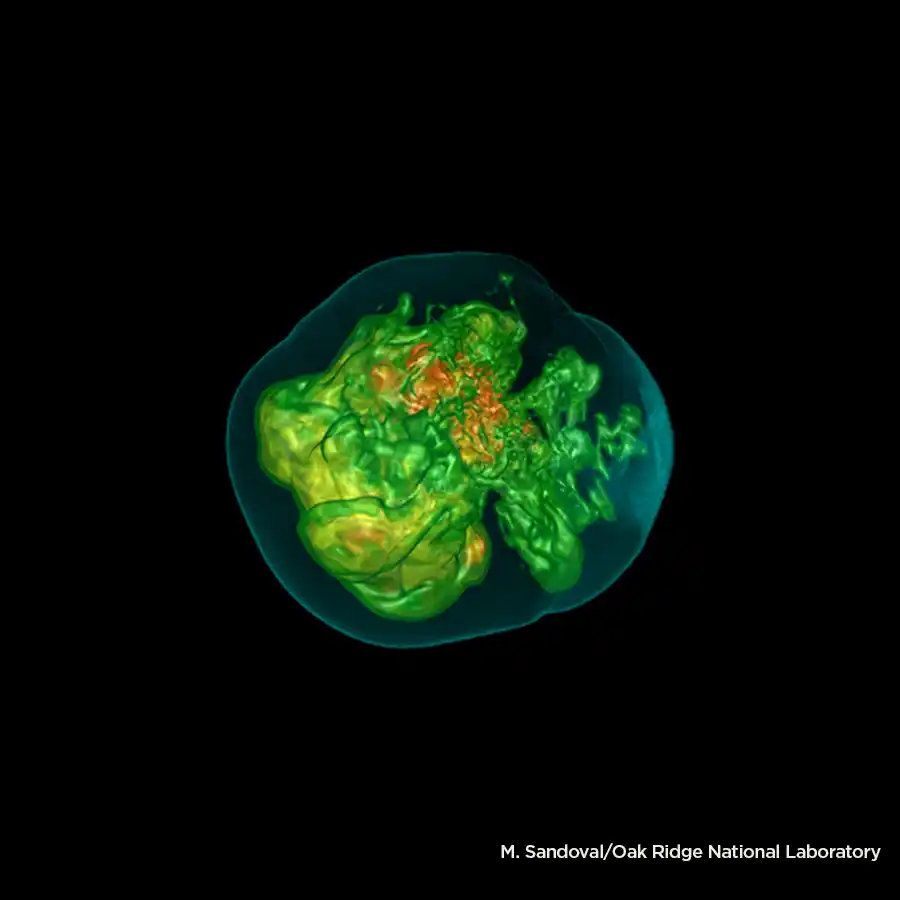

A nucleus isn’t one simple entity. Inside are protons and neutrons, formed by quarks bound together by gluons. That’s a lot of moving parts for structures so small that a typical grain of sand includes more than 10 million trillion of them.

Papenbrock said that like any system consisting of many particles, nuclei show different phenomena at different length (or energy) scales. To visualize this, consider the ocean. Papenbrock explained that seawater can appear as waves (on the scale of yards), eddies (which can range from tens of yards to inches in scale), and even motions of individual water molecules (microscopic scale).

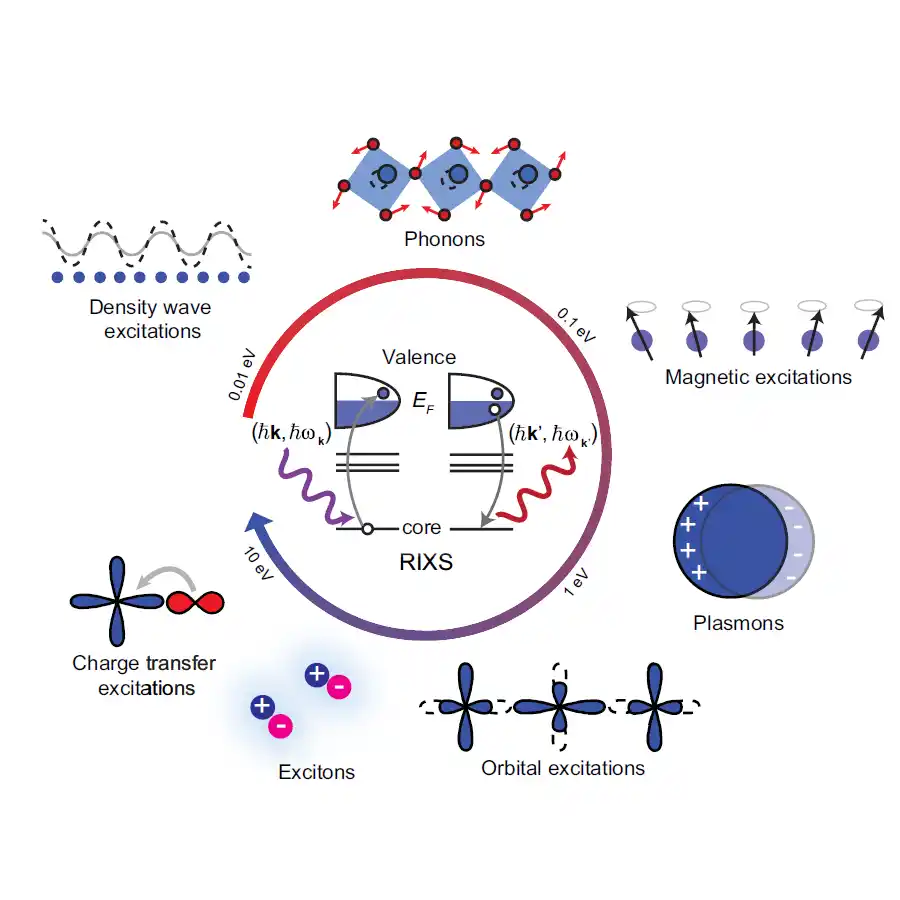

In a nucleus, different phenomena are realized at different energy scales. At low energy the entire nucleus might rotate. At the next energy level, many (but not all) of the particles vibrate. At even higher energies a nucleus (or a single proton or neutron) could break up.

“The more microscopic the approach one uses, starting at smaller length scales, the more cumbersome it is to compute these collective phenomena, such as eddies and waves in the case of water,” Papenbrock said.

A Computational Two-Step

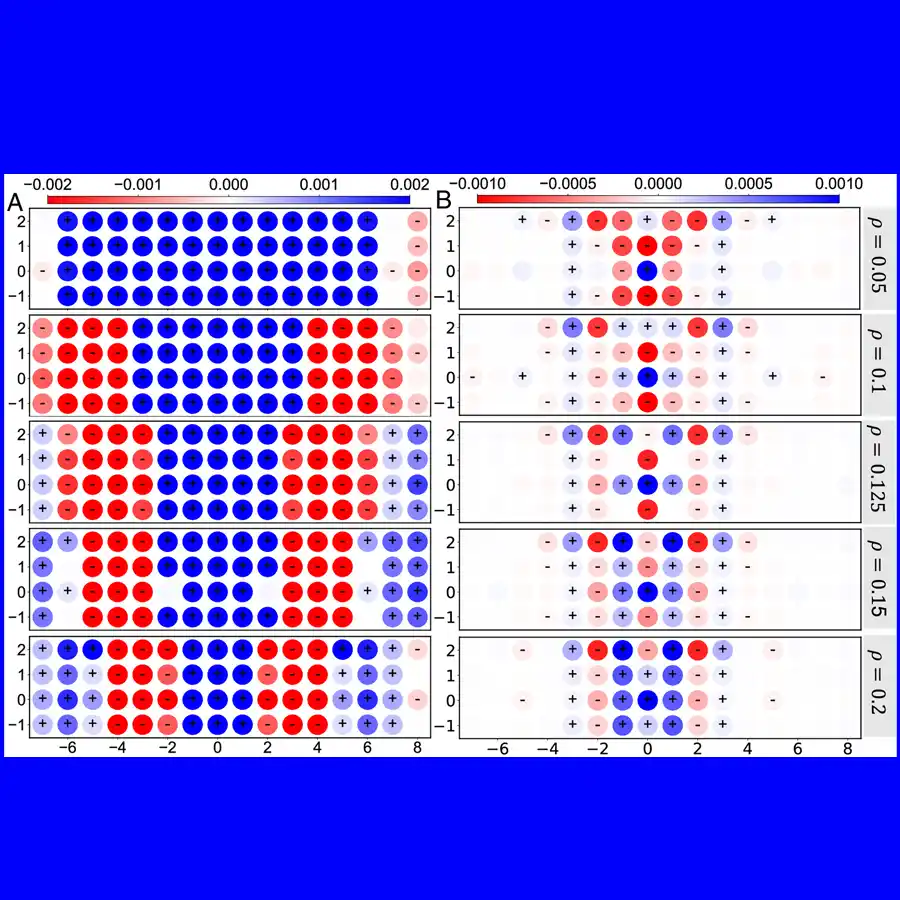

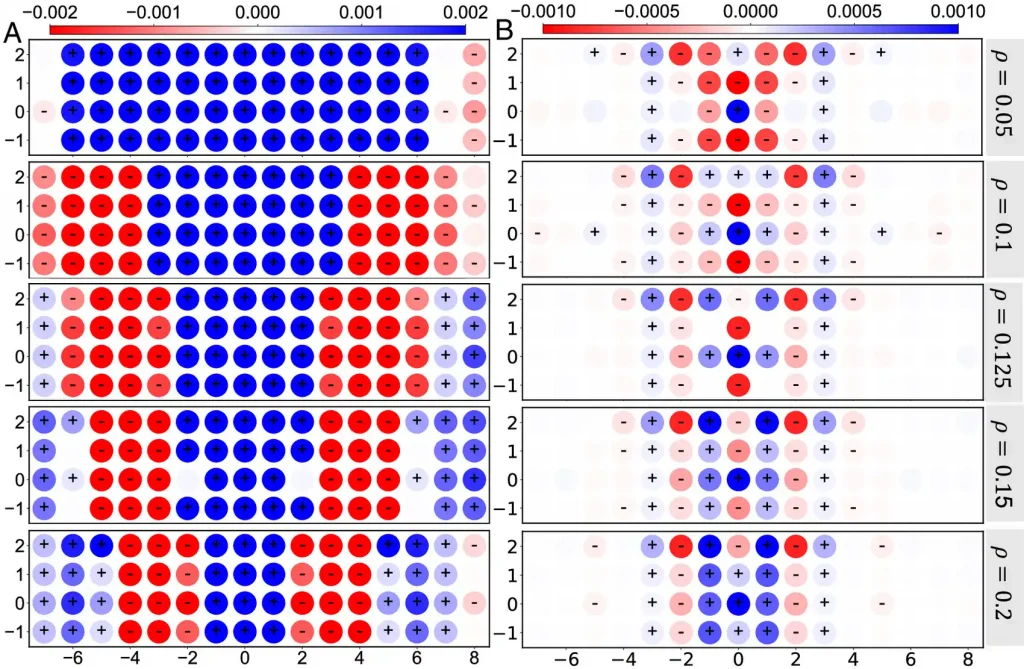

To tackle this cumbersome task, Papenbrock, Hagen, and their colleagues studied neon nuclei using the power of Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Frontier supercomputer. In a sort of computational two-step, they captured large energies by including short-range correlations and then computed the details by including long-range correlations. This approach gave them a high-resolution look into the intricate workings inside a nucleus.

A significant achievement in this work is that the team overcame a long-standing challenge in the field by describing multiscale physics with roots in quantum chromodynamics, or QCD. This is the fundamental theory of the strong nuclear force: one of the four forces of physics. It’s part of the Standard Model that describes all known particles and forces: the building blocks of matter and how they interact.

Papenbrock said that “one of the goals in nuclear physics is to describe phenomena starting from the most basic theories: in our case QCD. While we are not yet quite there, we used effective theories of QCD.”

He explained that earlier research computed nuclear binding and rotation energies, but relied on existing theories to model different phenomena at different energy scales. Here, he and his colleagues have developed a unified model that ties directly to bedrock theory.

The findings were published in Physical Review X and selected for a Physics Viewpoint highlight. Learn more about this research from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.