First Haslam Family Professorships for Physics

Tova Holmes and Yang Zhang have won the department’s first-ever Haslam Family Professorships, an investment that recognizes their past successes and deepens the impact of their future research and teaching.

The university’s Office of the Provost awards these honors in recognition of the recipients’ achievements in research, scholarship, and creative activity. Currently seven faculty members across the Knoxville campus hold these professorships. For both Holmes and Zhang, the five-year appointment began August 1, with the possibility of continuation past 2030.

Holmes is an associate professor who joined the department in 2020. She’s an experimentalist working in elementary particle (high energy) physics and has won a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Early Career Research Award, the university’s first-ever Cottrell Scholar Award, and a Sloan Research Fellowship, among other honors.

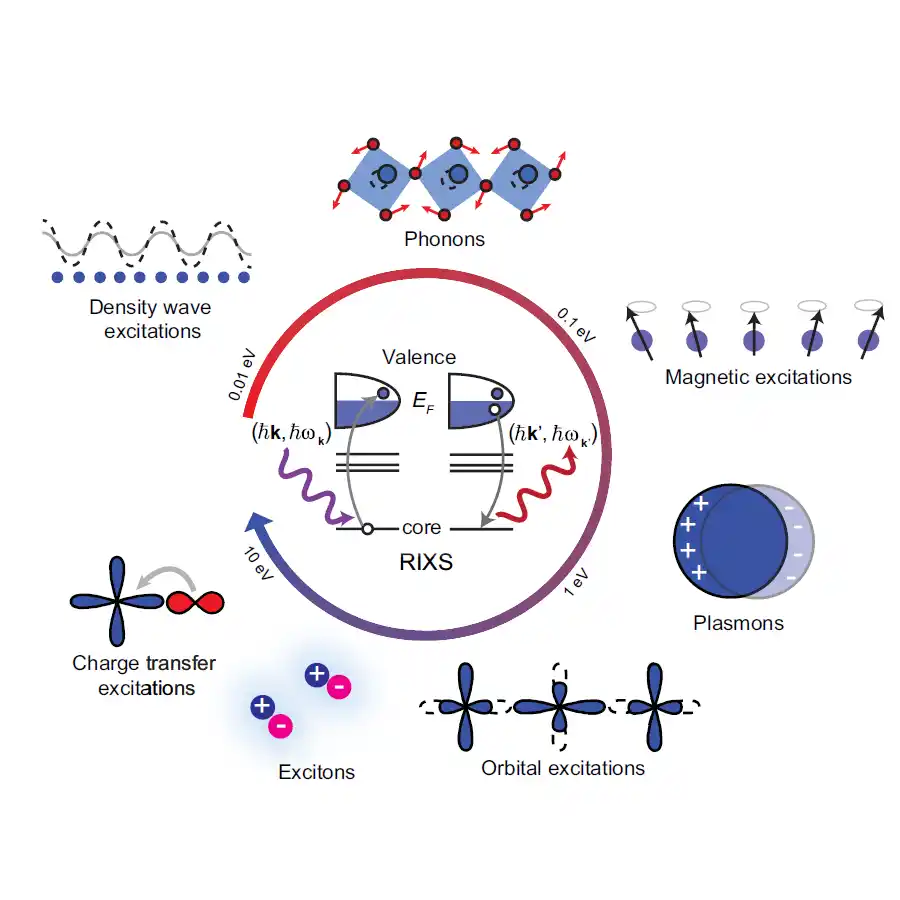

Zhang joined the department in 2023. An assistant professor, he’s a theorist in condensed matter physics focusing on quantum materials and artificial intelligence (AI). In 2024 he won the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) Early Career Scientist Prize in Computational Physics.

“This marks the first time (the Haslam Professorships) have been bestowed within our department, an exciting and well-deserved recognition of Tova’s and Yang’s remarkable accomplishments in high energy physics and quantum materials, respectively,” said Professor and Department Head Adrian Del Maestro. “These awards reflect the strong advocacy of Divisional Dean Kate Jones and Executive Dean R.J. Hinde, who worked with the Provost’s Office to implement a key recommendation from our recent Academic Program Review: that we do more to celebrate the outstanding contributions of our junior faculty.”

Small Things with Big Impact

Holmes is particularly gratified about the options the Haslam Professorship provides.

“Having a named professorship is a great honor just on its face, but it comes with extremely flexible funds that I can spend how I think will most benefit my program,” she said. “If a student has an amazing result that I want to make sure they can show off, I can send them to a conference. I can buy new equipment. I can do whatever I think is most useful to my group at the time and that is such a rarity. It lets you do these smaller things that can really have a big impact. It has an impact on your impact.”

Holmes’s research is firmly rooted in established science with an eye on the horizon. Her group works with the Compact Muon Solenoid detector program at CERN, a longstanding experiment that’s a DOE priority. They’re building a new hardware system that will reconstruct, in real time, every track from every particle that comes flying out of the particle collisions at the upgraded High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider, which will turn on in 2029. She’s also collaborating with scientists at Fermilab to study dark matter signatures and has become a leader in the effort to build a muon collider, part of the nation’s particle physics roadmap for the future.

While Holmes’s work dives into the particles and forces that compose and corral matter, Zhang looks at the complexities and promise of new materials, building a broad program across departments.

“Right now, I am most enthusiastic about the rapidly advancing intersection of quantum materials and artificial intelligence,” he said. “My group is developing new computational methods to understand and predict the behavior of complex quantum systems at a scale that was previously impossible.”

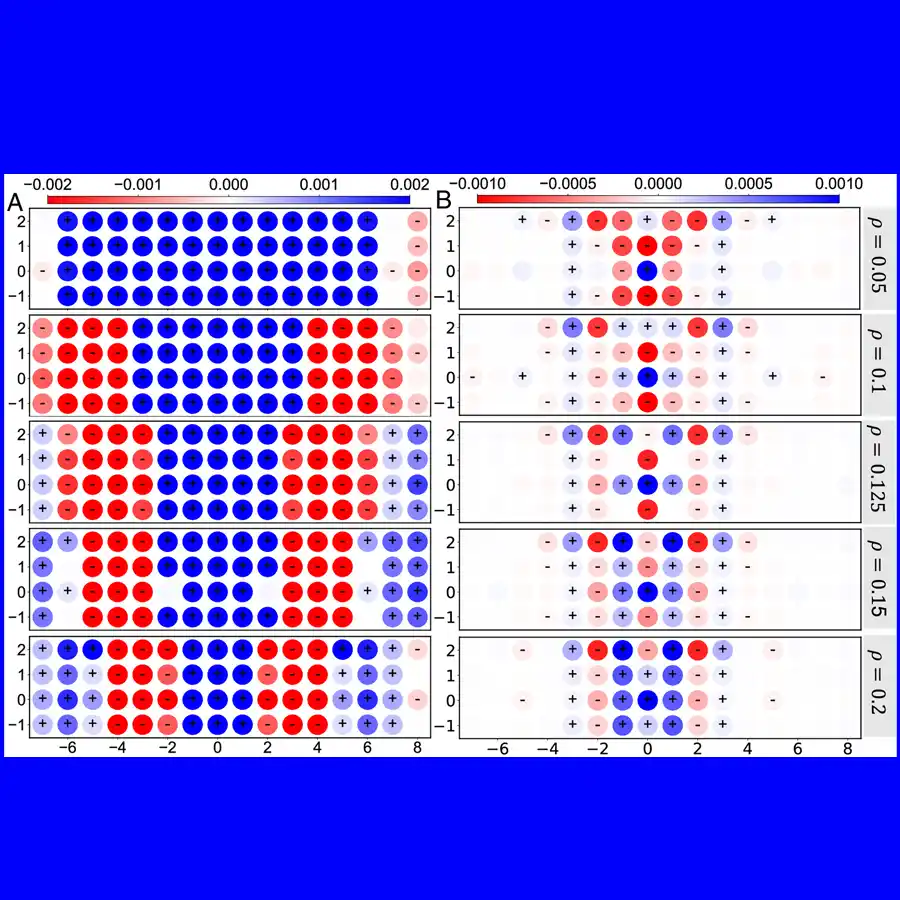

His team is particularly focused on moiré materials, which have atomically thin layers that are arranged slightly askew. The interactions between those layers give rise to new properties.

“We’ve discovered that you can create entirely new electronic properties just by twisting two-dimensional semiconductors,” Zhang explained. “This research is fundamentally interdisciplinary and (is) creating a new synergy between computational physics, computer science, and materials science. As I discussed at the Symposium on Machine Learning in Quantum Chemistry held in Knoxville, my work is a perfect example of this. We use high-level physics principles and data from smaller, exact calculations to train advanced machine learning models. These models then learn the complex quantum rules and interactions that govern materials.”

Outpacing the Textbooks

For Holmes and Zhang, thriving research spills over into their classrooms.

“I’m teaching particle physics right now, which is an utter delight,” Holmes said.

When she first joined the faculty, getting back to the classroom helped reacquaint her with concepts she learned as an undergraduate and tie them to her current elementary particle pursuits.

“I am so glad to be at a university where I’m teaching, because it’s my job to constantly refresh and expand my understanding of the underlying elegance of particle physics and the fundamental principles underpinning it,” she said. “I’ve been able to make more connections between my work and other fields in particle physics. I love being able to incorporate ideas from research into classes.”

Zhang’s research also heavily influences what and how his students learn.

“My research and teaching are deeply intertwined,” he said. “This field is moving so quickly that the most exciting topics, whether it’s AI in physics or the discovery of new quantum materials, are not in the standard textbooks yet. I bring these frontier problems directly into the classroom. When my research group develops a new computational tool, I often turn that into a lab module or a final project for my students. This gives them hands-on experience with the exact methods that are driving discovery today. My goal is to not just teach them established physics but to train them as the next generation of computational scientists who are fluent in physics, math, and AI.”

Long before winning a Haslam Professorship, Holmes was aware of what the name meant for education.

“I understand that as governor Bill Haslam did a lot to increase access to the University of Tennessee for the students of the state,” she said. “I really respect that effort and it was something I was impressed by when I arrived in Tennessee; what an incredible set of programs there were to give access to the university to everybody in the state. That’s a thing I’m very pleased to have attached to the name of this.”

For Zhang, the honor is inspiration to keep doing good work.

“This kind of support from the Haslam family is truly transformative,” he said. “A named professorship like this feels like a holistic recognition of one’s overall contributions; not just a single project, but the entirety of my research, teaching, and service to the department and the university. It is less about what you will do and more about an investment in how you work and your potential as a faculty member. That is incredibly meaningful and encouraging.”

Zhang also sees these named professorships as a reflection of the department’s upward trajectory and its collaborative culture.

“I want to thank Adrian Del Maestro and all my colleagues for making this department such an innovative place to be,” he said. “Most of all, this honor is a credit to the brilliant students and postdocs I am lucky to work with every day.”