A Front Row Seat to Quantum Behavior

Helium may bring the fun to party balloons but we’re actually more familiar with its serious side. As a liquid it’s crucial to cooling magnets used in magnetic resonance imaging and manufacturing semiconductors. Cooled to a critical temperature it can become a superfluid: flowing with no viscosity and losing no kinetic energy.

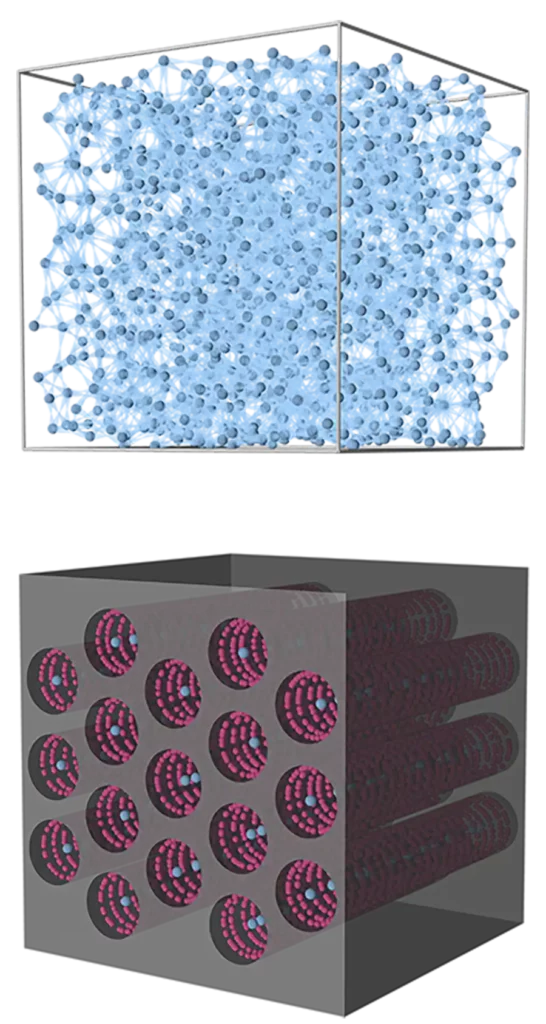

For Professor Adrian Del Maestro, helium holds even more exotic charms. Since his postdoctoral days he’s wanted to confine this element to one dimension, where theory predicts it will become a fluctuating phase of matter that’s not exactly a solid, a liquid, or a superfluid. The model itself (a Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid) was first proposed in 1950 and until now has never been seen in a system of strongly-interacting atoms. Del Maestro and his colleagues at Indiana University Bloomington have found a way to squeeze helium down to single-atom thickness and give scientists a front-row seat to observe quantum mechanical behavior.

Building an Atomic Scale Pipe

The promise (and challenge) of quantum science lies in understanding how things work in lower dimensions. Take carbon, for example. In 3-D it’s graphite, the soft stuff that lets a pencil glide across paper. In 2-D it’s graphene, an ultra-light and ultra-strong system.

“A sheet of graphene weighing less than the whisker of a cat could support the cat’s weight,” Del Maestro explained.

Helium has similar differences.

“In 3-D, the same helium atoms that fill balloons can whiz around each other to form a superfluid phase of matter,” he said. “In 1-D, the atoms are forced to interact strongly as they are all made to stand in a line, and they can’t easily exchange places.”

Though its properties make helium an ideal system for getting a glimpse into one-dimensional behavior, confining its atoms to this scale is no trivial task.

“You literally need to make a pipe that is only a few atoms wide,” Del Maestro said. “No normal liquid would ever flow through such a narrow pipe as friction would prevent it.”

Fortunately, in 2015 he met IU’s Paul Sokol at a conference and they merged their theoretical and experimental expertise to build this atomic structure.

“Paul had worked on confining superfluids for years, but just couldn’t get them small enough,” Del Maestro said. “I had done numerical simulations that found the ‘sweet’ spot on the pipe size we needed.”

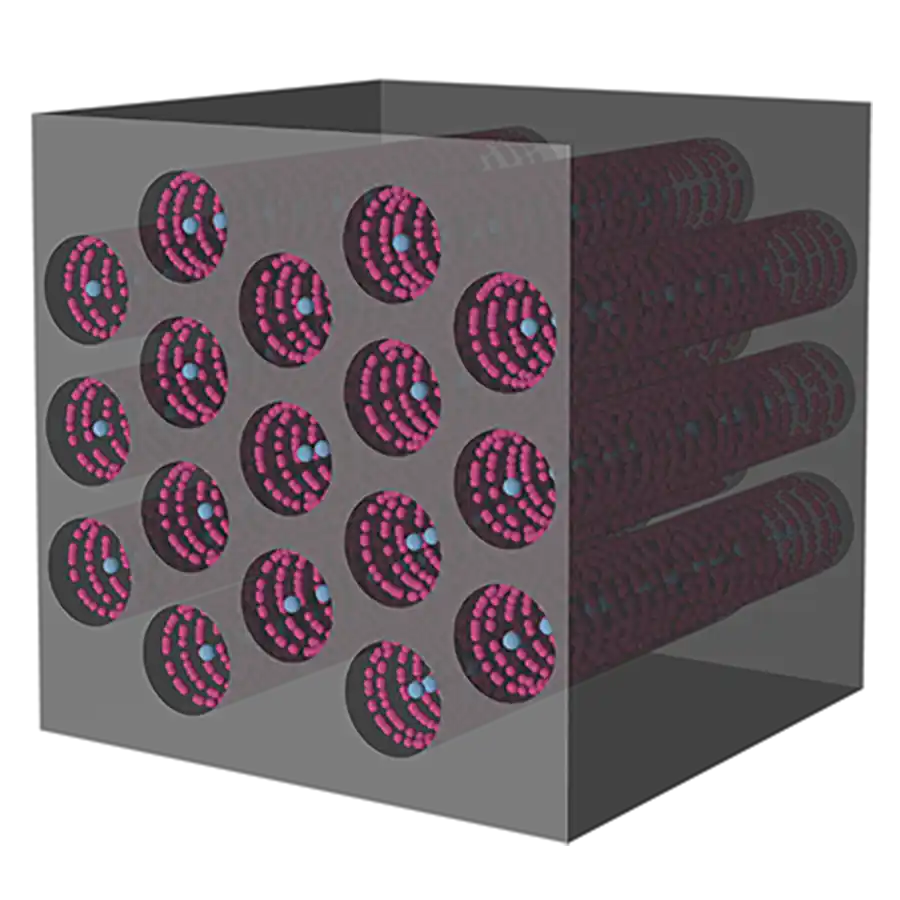

Del Maestro suggested they paint the inside of a pipe to make it smaller. Sokol came up with the idea to pre-plate it with a rare gas. They took a nanoporous material, whose structure is like a sponge with ordered pores, and coated the inside with a perfect layer of argon to make it angstrom scale (a hundred-millionth of a centimeter). Now they had their 1-D pipe. They filled it with liquid helium, which adsorbed inside the pre-plated nanopores, and then bombarded the helium with neutrons. The resulting excitations told them what phase of matter they had.

“You can think of this as testing whether something is a liquid or solid by asking what happens when you throw something at it,” Del Maestro said. “Does it bounce off, or travel through? The results of the experiments can be modeled with theoretical calculations and simulations to confirm the existence of the Luttinger liquid state of matter.”

The Power of Positive Thinking

Del Maestro explained that helium confined in one dimension holds possibilities that other systems exhibiting 1-D do not.

“It can be adjusted with pressure, all the way from a gas to a solid … and provide the possibility for tuning and optimizing devices exploiting quantum phenomena,” he said.

A one-dimensional pipe filled with liquid helium attached to a device can also sense tiny rotations, pointing to future applications in geo-sensing, gyroscopes, and autonomous navigation in extreme environments where GPS isn’t feasible, such as drones on other planets.

The isotopes helium-3 and helium-4 offer the chance to further test the Luttinger liquid theory that a 1-D liquid of bosons and fermions—particles that make up matter and carry forces—should have similar behavior at low temperatures. Del Maestro and Sokol have opened an avenue for this research with the experimental realization of 1-D helium. The findings, published in Nature Communications, were the result of work from their respective groups, as well as patience, persistence, and positive thinking.

“It’s something I’ve been thinking about for 15 years … and was only possible because of the tight integration of theory and experiment,” Del Maestro said. “I’d ask Paul if something was possible, and he would say ‘No, but I’ll think about it.’ Paul would show me some crazy result and say ‘Do you know what is going on at the atomic level?’ and I would reply with ‘No, but I’ll think about it.’”

Eventually, he said, all the pieces of this 1-D puzzle fit together.